"The news spread like measles and was just as welcome: Have you heard? They want to build a big dam. It will

flood our valley."

In 1969, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers proposed a plan to build four large dams in the Unadilla Valley portion

of the Susquehanna River basin for flood control and drinking water between Binghamton, N.Y., and Baltimore, Md.,

and recreational opportunties in the regions surrounding the reservoirs.

Concerned valley residents renounced the plan, echoing sentiments like the above one from Alice Hiteman, a long-time

area resident. Worried over the possibility of losing their homes, farms, businesses and local history, Mrs. Hiteman

and other valley residents united to fight the plan.

The following story chronicles the events that year which led to the formation of the Upper Unadilla Valley Association

(UUVA), a non-profit organization that, 30 years later, still works to preserve and protect the Upper Unadilla

Valley's historic and natural resources. Information was provided by Ruth (Plumley) Starkweather and Mrs. Hiteman,

two original members who continue to serve on the association's board of directors; The West Winfield Star; and

the agenda from the UUVA's initial public information meeting held on Aug. 12, 1969. The story was compiled and

edited by Wendy Barrett, a UUVA director since 1997 and editor of "Saving Our Valley."

To folks who lived through the ordeal, Betty Tamsett will always be remembered as the "Paul Revere" of

the region. Mrs. Tamsett, a South New Berlin resident and Sherburne-Earlville Central School guidance counselor

at the time, learned of the proposed dams, including a proposed site in nearby West Edmeston, through the news

media. Suspecting that valley residents to the north were unaware of the plan, she began randomly telephoning listings

from the "Classified" section of her phone book to alert communities along the Unadilla River and other

tributaries of the Susquehanna.

The Leonardsville Hardware Company was among those she reached. On hearing the news, store owner Ruth (Plumley)

Starkweather contacted other Leonardsville residents, including Harold Davies, who in turn relayed the information

to Walter Jones during a visit to the Jones & Slosek General Store in Unadilla Forks. Several customers there

overheard the story, as well.

Nearby, another Forks resident, Howard Goff, was atop a ladder putting a fresh coat of paint on his early 1800s

home, situated along the bank of an old mill pond.

Someone called to Howard, "Did you know that they are going to build a dam on the Unadilla? Your house will

be under water!"

Mr. Goff, who recently had retired as a school administrator, stopped painting and joined the general store group,

which was pondering how to avert the impending project.

They decided to fight the plan by forming a group of concerned citizens from five local communities: West Winfield,

Bridgewater, Unadilla Forks, Leonardsville and West Edmeston. Mr. Goff would be its president; Halbert "Bud"

Hiteman, Alice Hiteman¹s husband, its vice president; Charlotte Brown, the secretary; and Clair Barrell, treasurer.

The executive committee representing the various communities included Halbert Hiteman, Francis Combar and Betty

Tripp for Bridgewater; Harold Davies, Frederick Degen, Theresa Johnson and Dr. Eugene Evans for Leonardsville;

Howard Goff, Charlotte Brown and Gertrude Gilson for Unadilla Forks; and Clair Barrell, Percy Pugh and Hazel Welch

for West Edmeston. The Upper Unadilla Valley Association was born.

Residents to the south already were at work reviving the Tri-County Watershed Association, which had thwarted a

similar plan 20 years earlier. The two associations met frequently and traveled to public forums in Oneonta and

Binghamton to gather more information and voice opposition to the corps' latest proposal.

"At one public meeting, Colonel Love, of the Army Corps of Engineers, presented a slide show that featured

another dam he engineered," said Mrs. Hiteman. "He commented how the lake it created enhanced the beauty

of the valley. We didn't see things that way for our valley."

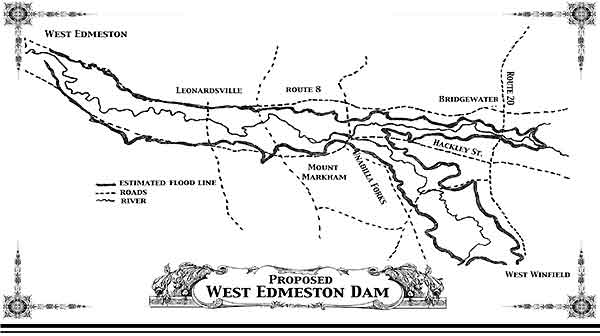

The proposed Unadilla River dams would have flooded the Unadilla Valley from the Madison-Chenango counties line

to the upper reaches of the east and west branches of the river, effectively submerging communities like Leonardsville

and Unadilla Forks, as well as valley farm land in the Mount Upton, New Berlin, East Guilford, Cope's Corners and

Gilbertsville areas. In addition, summer "let-downs," in which collected water would be released, would

have transformed hundreds of square miles of the scenic valley into vast mud flats every year.

"Col. Love never explained what kind of recreation would exist during letdown,"said Mrs. Hiteman."

During the discussion that followed, a gracious woman rose from her seat and announced, 'You are a fine group of

gentleman. I¹d be happy to invite you to dinner, but I do not want your dam.'"

In the months that followed, the association met many times. Members contacted their legislators and wrote to local

newspapers suggesting alternate flood-control solutions, such as restoring the many small mill ponds along the

Unadilla River and planting trees to promote the in-soak of rain water. They also called attention to the value

of the area's farmland and how the reservoirs would hurt the farm economy and displace homeowners.

"Nothing about the dams were for the benefit of the areas in which they were built," said Ruth Starkweather.

The Army Corps of Engineers, which already had spent $4 million to determine locations for the dams, was set to

ask Congress for $225 million for the project by June 1970.

Mrs. Hiteman recalled the apprehension she felt at the time. "From our house on Route 8, I looked eastward

from a window of our old farmhouse toward the river. Our cropland and the woods where the white trillium grow all

would be under water. Would it reach our home, too, this place that had sheltered so many generations and so much

living? I watched the meandering river that flowed amid fertile farmland and, here and there, through virtual wilderness.

Gentle hills with sweet-flowing springs of water, some of which have sustained residents since the time of the

earliest settlers, hugged the valley on either side."

In February 1970, Halbert Hiteman represented the UUVA at a public hearing that drew three speakers who favored

the Army Corps' proposal and 22 who opposed it. The hearing, held in Albany, N.Y., was called by state Assemblyman

Clarence D. Lane, a Republican from Windham who chaired the Assembly's Environmental Conservation Standing Committee.

Mr. Hiteman and Lloyd Crumb, a former Leonardsville resident who was a consulting engineer with a private civil-engineering

firm in Syracuse, testified "against the validity of the 'big' dam approach to water conservation," according

to a published account in the Feb. 12, 1970, issue of The West Winfield Star.

Both men also submitted written briefs. Mr. Hiteman¹s brief said the UUVA's 520 members who lived or earned

a living in the Upper Unadilla Valley were "unequivocally opposed to flooding extremely valuable agricultural

and forest lands and destroying productive land to satisfy questionable statistical population and water shortage

projections." He noted agriculture's value to the state's economy as an annual $3.5 billion industry.

"To farm successfully and competitively today, a farmer requires the large, fertile, level fields of the valley

floors, rather than engineers and conservationists" suggesting that these fields become the floors of large

lakes whose water level fluctuates at the whim of a gatekeeper," Mr. Hiteman wrote. "These land areas

ought to be those which are granted an agricultural priority protecting them forever for future food needs and

as land areas that preserve the ecological balance of our environment."

Mr. Crumb argued that no comprehensive economic analysis of the proposal had been made.

"Such reports would show the assessed valuation lost to the local governments and the costs to the counties

and state to relocate roads and bridges...for school districts to rebuild central school buildings... of compensating

churches to rebuild their facilities...of relocating cemeteries...." he wrote. "The best farmland...is

on the valley floor. Consider the loss of economic productivity of the townships and counties. The areas under

discussion are not unproductive vacant lands.... They are the center cut of New York State. This is the source

of the State¹s Tax Dollar income."

He concluded by suggesting that extensive engineering reports and impact studies be submitted to the state Legislature

and affected counties and towns to determine their tax revenue loss and to compare big dam construction with alternative

storage capacity that could be achieved by restoring old mill ponds and small dams on the valley floor and along

feeder brooks upstream.

Two weeks later, The West Winfield Star reported that Assembly-man Lane remained unconvinced of the need for the

dams and would recommend to his committee that legislation be prepared to "stop or slow down many of the projects,

possibly by prohibiting some of them or by having them be subjected to approval by county legislatures or local

referendums."

In the long run, the value of the area's farmland saved the valley floor. The July 16, 1970, West Winfield Star

reported that "the Army Corps of Engineers' plan for a dam in the West Edmeston area had been discarded 'because

it would destroy too much farmland.'

On the first review it was retained, and on the second review, it was discarded."

Ed Blackmer, an engineer with the federal government at that time and now an engineer with the New York State Department

of Environmental Conservation, said the state had been involved with the proposal in the environmental review process.

He said federal legislation eventually permitted construction of a certain number of dams in the Susquehanna River

basin, but the proposed West Edmeston dam probably was shelved because it failed to show a positive cost-benefit

ratio.

"The flood benefit had to be equal to or greater than the cost of the project," he said. "People

started to question some of their numbers, including land right costs, and the Army Corps probably gave up on the

plan when it realized it would have to pay more than it thought for land and easements."

When the Army Corps took its shovels and went away, valley residents breathed a great sigh of relief.

"We got so we were a small army fighting against the other army," said Mrs. Hiteman. "We just kind

of hammered at it. I think if we hadn't done anything, they would've gone ahead with the project."

Up and down the valley today, communities ranging from small hamlets and cities to medium-sized villages and towns

retain some measure of the quiet way of life that appeals to its long-time residents.

"The area is still filled with graceful examples of early architecture, and we still have some of the best

farms in the state, even as an increasing number of family farms have succumbed to economic pressures," said

Mrs. Hiteman.

The Upper Unadilla Valley Association remains intact, too. Some original members, including Mrs. Starkweather and

Mrs. Hiteman, have served on its board for many years. The board also retains two of its original directors: Percy

Pugh and Fran Combar. All the original officers---- Howard Goff, Halbert Hiteman, Charlotte Brown and Clair Barrell----

have since died, but their strong leadership, hard work and dedication to saving the valley won't soon be forgotten.

Their spirit lives on in the Upper Unadilla Valley Association.